Odia Researcher Retraces Lost River Saraswati Of Harappan Civilisation

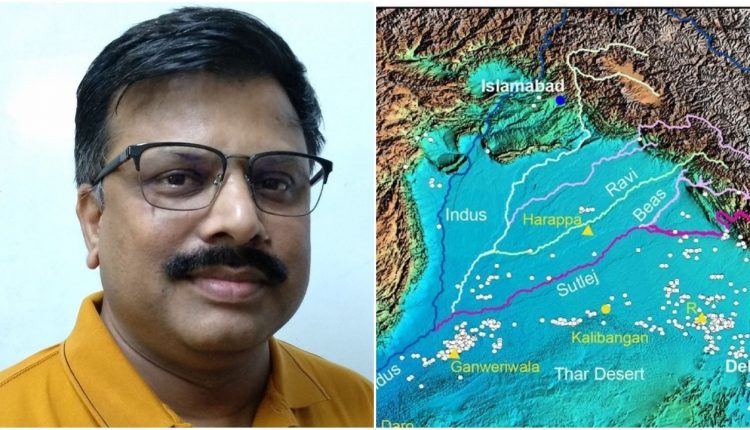

Perhaps for the first time, it has been established that India’s fabled prehistoric river Saraswati did actually exist. The credit for the research goes to a team led by Odia scientist, Prof. Jyotiranjan S. Ray, his Ph.D. student Dr. Anirban Chatterjee from the Physical Research Laboratory (PRL), Ahmedabad and two other co-workers. The research establishes that “there existed a strong and perennial river in the plains of northwestern India, roughly along the course of the modern Ghaggar.” These results have been published in a recent issue of the internationally reputed journal, Nature Scientific Reports.

How did they do it?

They analysed sand from 3-10m below the surface of Ghaggar, using isotope techniques (a technique employed for studying rivers water resources) and found that the ancient Ghaggar was indeed a perennial river, fed by the glacial-melt water from the Himalayas. They detected grey coloured, coarse-grained sand layers containing abundant white mica along a 300 km stretch upto the Pakistan border. The presence of this sand, that is typical of glacial fed higher Himalayan rivers like Ganga, Yarnuna, and Sutlej, gives compelling evidence of a mighty river in the past. Dating the mica samples present in the sand, the researchers found ages consistent with that of the rocks of the Higher Himalayas.

Enough Evidence

The isotopic ratios of the sands also reflected compositions of their source rocks present in the glaciated regions of the Higher Himalayas. These findings suggest that these sands were transported by the river from the Higher Himalayas to the plains. And rivers that originate from such regions remain active round the year and don’t depend specifically on the monsoons.

Mighty River

Another breakthrough result from this research also establishes a checkered past of this seemingly powerful river. The depositional age of these grey sand layers indicates that the river had uninterrupted flow prior to 80,000 until 20,000 years ago. It waned subsequently due to extreme aridity of the last glacial period. This had also affected water flow in all the major Himalayan rivers. The flow of the river regained its strength around 9,000 years ago and remained so for the next 4,500 years before losing its vigour again.

Ghaggar Connection

Considering that the modern Ghaggar has no direct connection to the Higher Himalayas and probably was not connected to it in the past as well, the only likely pathways for the glacier-melt water in the ancient Ghaggar could have been through the distributaries of the Sutlej, the neighbouring mighty Higher Himalayan river. This is confirmed by the identical ratio of clams that grew in the ancient Ghaggar to that of the water of the Sutlej. The final decline of the runoff in the ancient Ghaggar was probably due to rapid abandonment of channels by the distributaries of the Sutlej, away from it.

Fabled River

The most celebrated river of prehistoric India, the Saraswati, is mentioned for the first time in the most ancient Indian text, the Rig Veda. Later texts such as the Mahabharata go on to describe its dwindling flow until its complete disappearance. It was only in the nineteenth century, when British explorers proposed its prehistoric existence along the river Ghaggar, a modern seasonal stream in northwestern India, that the river was considered real.

Harappan Civilisation Link

Interestingly, the dry channels of this purported round-the-year flowing (or perennial) the Saraswati were discovered within the ruins of the Harappan Civilisation, the earliest known urban settlement in the Indian subcontinent. Most archaeologists believe in the Harappan Civilisation-Saraswati-Ghaggar connection. However, the lack of direct evidence for the perennial past of the river Ghaggar and the fact that the Indian summer monsoon was very weak during the mature phase of the civilisation (4,600 to 3,900 years ago), had led many to reject the very idea of the river Saraswati and its hypothesised relationship with the Harappan culture.

Analysing the dynamics of settlements of the Harappan Civilisation, researchers have determined the time duration of the revival of the ancient Ghaggar (9,000 to 4,500 years ago).

Comments are closed.